|

RANANIM

|

| THE BULLETIN, DH LAWRENCE & KANGAROO |

|---|

Photo: Rose Shead

| The dinner at the Union University & Schools Club, Sydney, on Thursday August 2016, to celebrate the launch of Robert Darroch's two volume DH Lawrence's 99 Days in Australia and to commemorate Lawrence's admiration for The Buletin which he quoted from in Kanagroo. Amomg the guesys were artists Paul Delprat (standing, left ) and Garry Shead, and former Bulletin luminaries: Trevor Kennedy, Trevor Sykes, Lindsay Foyle, John Edwards, Deborah Hope, Goeffrey Lehmann, Evan Williams and Robert Darroch. Sandra Jobson (Darroch) paid tribute to the leading Australian artists and musicians who were inspired by Lawrence, including Sidney Nolamn, Brett Whiteley, Garry Shead, Paul Delprat, sculptor Tom Bass and Peter Sculthorpe |

|---|

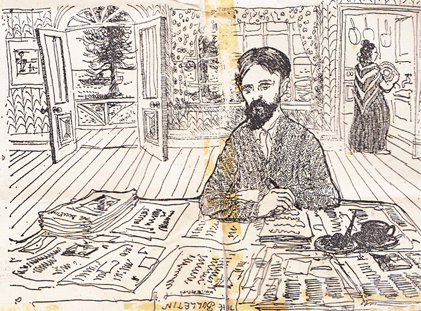

Lawrence reading The Bulletin at Wyewurk Drawing by Pauld Dekprat THE INFLUENCE of The Bulletin in Lawrence’s 1923 Australian novel, Kangaroo – his 8th major novel –is substantial and pervasive. The role The Bulletin played in my story of how Kangaroo came to be created is also profound. "What's his name?" "Cooley--Ben--Benjamin Cooley." "They like him on the Bulletin, don't they? Didn't I see something about There is something especially interesting about this Bulletin reference. In an almost desperate effort to disparage the Darroch Thesis, the annointed Cambridge University Press editor of the 1994 “definitive” edition of Kangaroo, Bruce Steele, said I was wrong about Rosenthal, and that if Lawrence had anyone in mind when he created the character Cooley, it would have been Sir John Monash, not Rosenthal. At one point the Somers character – who is Lawrence – receives mail from England, which offends him. He writes: Although Lawrence hadn’t a clue what he had run across in Australia (he did not know what a secret army was), he recognised that The Bulletin had an irreverent streak. At one point he is talking to the trade union leader “Willie” Struthers (actually “Jock” Garden) who tells him: In the most important chapter in the novel – when Somers comes up to town to confront Cooley/Rosenthal – he goes to the GPO to buy some stamps, then comes out and walks down Martin Place, where he sees “the pink spread of Bulletins for sale at the corner of George Street” (where he buys a copy to read back in Thirroul). Two chapters later, now deprived of any further secret army material from Rosenthal and his secret army, he pads out the narrative with an entire chapter filched from the famous Aboriginalities page of The Bulletin. He called the chapter “Bits” and it starts: …he looked at the big pink spread of his Sydney Bulletin viciously. The Bulletin was the only periodical in the world that really amused him. The horrible stuffiness of English newspapers he could not stand: they had the same effect on him as fish-balls in a restaurant, loathsome stuffy fare. English magazines were too piffling, too imbecile. But the "Bully", even if it was made up all of bits, and had neither head nor tail nor feet nor wings, was still a lively creature. He liked its straightforwardness and the kick in some of its tantrums. It beat no solemn drums. It had no deadly earnestness. It was just stoical, and spitefully humorous. Yes, at the moment he liked the Bulletin better than any paper he knew, though even the Bulletin tried a dowdy bit of swagger sometimes, especially on the pink page. But then the pink page was just "literary" and who cares? [it was actually The Bulletin’s famous Red Page, which carried its (substantial) weekly literary content] So he rushed to read the "bits". They would make Bishop Latimer forget himself and his martyrdom at the stake. (This “Bits” paragraph was inspired by the copy of The Bulletin he had bought outside the GPO the previous Saturday.) He quoted precisely eight separate “Bits” in this chapter, all word-for-word and from the same issue of The Bulletin: “Bits about bullock drivers and the biggest loads on record, about the biggest piece of land ploughed by a man in a day, recipes for mange in horses, twins, turnips, accidents to reverend clergymen, and so on.” He even cited cartoons in The Bulletin: “Then a little cartoon of Ivan, the Russian workman, going for a tram-drive, and taking huge bundles of money with him, sackfuls of roubles, to pay the fare. The "Bully" was sardonic about Bolshevism.” One “Bit” was sent in by someone who called themselves “Cellu Lloyd” (all Bulletin Bits contributors were given such nicknames). He (apparently) wrote: Before you close down on mangey horses here's a cure I've never known to fail. To one bullock's gall add kerosene to make up a full pint. Heat sufficiently to enable it to mix well, not forgetting, of course, that half of it is kerosene. When well mixed add one teaspoonful of chrysophanic acid. Bottle and shake well. Before applying take a hard scrubbing brush and thoroughly scrub the part with carbolic soap and hot water, and when applying the mixture use the brush again. Lawrence added: “This recipe brought many biting comments in later issues.” Which implied he was a regular Bulletin reader. He acknowledged, however, that the Bulletin’s sub-editors recognised that some of their readers were a little flaky when it came to grammar and syntax. “Somers liked the concise, laconic style. It seemed to him manly and without trimmings. Put ship-shape in the office, no doubt.” Another “Bit” he cited showed he had learned something about the Australian character. Lady (who has just opened door to country girl carrying suitcase): "I am Girl: "I'm her; and you're not. The 'ouse is too big." There, thought Somers, you have the whole spirit of Australian labour. His final comment about The Bulletin came at the end of chapter 16. By this time he had some inkling of what those “horrible paws” represented. He had become disillusioned about Australia and its politics and people. He wrote: “Somers, looking through the Bulletin, though he could hardly read it now, as if he could not SEE it, in its one level, as if he had gone deaf to its note.” The silvery freedom had suddenly turned ugly. That, however, was not quite right. While in Australia he also read copies of the Sydney Daily Telegraph, The Sun and the Sydney Morning Herald (this was delivered to his door every day he was in Thirroul). He was keen to keep in touch with events around him. One chapter in Kangaroo is called “Volcanic Evidence” and it contains a long extract from the Telegraph about volcanoes – word-for-word, including the journalist’s byline and cross-heads! More significantly, the important chapter, “The Row in Town” – describing a riot in the Trades Hall (which is the climax of the novel) - is derived from reading back copies of The Sun in its office in Castlereagh Street. (He acknowledged this source, but tried to disguise it by changing the paper’s politics from conservative to “the radical paper”.) A few chapters earlier he cites a swag of headlines from a June issue of the SMH. In fact, there should have been a lot more from The Bulletin in Kangaroo. Indeed, he even contemplated the possibility of working for The Bulletin, or at least writing for it while he was in Sydney. Before he came to Sydney, his main contact in Perth – “Pussy” Jenkins – gave him a letter-of-introduction to a senior staff member of The Bulletin, Bert Toy. (He later confessed to Mrs Jenkins that he had not “presented” the introductory letter – given to him probably in case he wanted some part-time journalistic work in Sydney – for within a few days of arriving he had the germs of a possible plot for his projected “romance”: the secret army he had stumbled on.) But it was probably Bert Toy, alerted by Mrs Jenkins about Lawrence’s arrival in Sydney, who was responsible for the only two items about Lawrence published while he was in the There is one last connection between The Bulletin and Lawrence and Kangaroo. It was in a letter in the manuscript collection of the Mitchell Library from the then assistant-editor of The Bulletin – Malcolm Ellis – to the second main character in Lawrence’s novel of Australia that in early 1976 I first read the name of the secret army that he ran across in Sydney. Ellis, writing to his friend Jack Scott (Jack Callcott in Kangaroo) said he hoped that Scott’s upcoming trip to Japan was being paid for by “The Garage”. (The secret army was in essence a mobilisation plan based on car-ownership, and its members “reported in” at the neighbourhood garage of one of its more mobile secret soldiers.) Scott was Rosenthal’s 2-i-c in “The Garage” hierarchy. Lawrence in Kangaroo gave Callcott’s profession as “a partner in a motor works place”.

Contemporary Bulletin cartoon lampooning the imperialist |

|---|

| If you wish to join the DH Lawrence Society of Australia, it's free. Just send us your email address. Click HERE |